Winners & Losers.

How to identify Trillion dollar startups & build the future.

What separates a multi-Trillion dollar company like Apple or Microsoft from the hip bar down the street?

Well, it’s not as complicated as you might think, it ultimately comes down to collecting five core “infinity stones”— CENTS.

Control is the ability to exist by yourself, without being reliant on other platforms.

Building on top of another person’s success is extremely tempting, it’s a growth hack.

Why start with zero users when you could build on top of an already proven business model with paying users?

The reason is while this is tempting, it also tempts fate— by building on top of another platform you not only get growth, you also get one giant risk— the platform you’re building on can turn off your power switch any time they want.

You’re at their mercy.

There’s a sea of tens of thousands of once-hot startups that built on top of other companies and paid the price for doing so.

To give a counter-argument, most startups do at first build on top of other companies’ successes for an initial user base— but they quickly diversify and establish independence as soon as possible.

PayPal started with building payments for eBay sellers, Activision Blizzard started with building games for Atari gamers, and Tesla started with building on Lotus chassis.

Almost every startup latches onto another company’s platform for initial growth. But you can only ride on their train for so long before you have to hop off.

Managing Control ultimately means not building on top of other platforms.

Don’t build a browser extension and don’t build a marketing agency/software for social media platforms—and don’t build on top of someone else’s platform.

Sacrificing Control for growth is tempting and addictive.

It’s a growth hack to drink the Kool-Aid and build on top of another platform to get users— once started it’s extremely hard to stop.

But eventually, the Kool-Aid is spiked with cyanide.

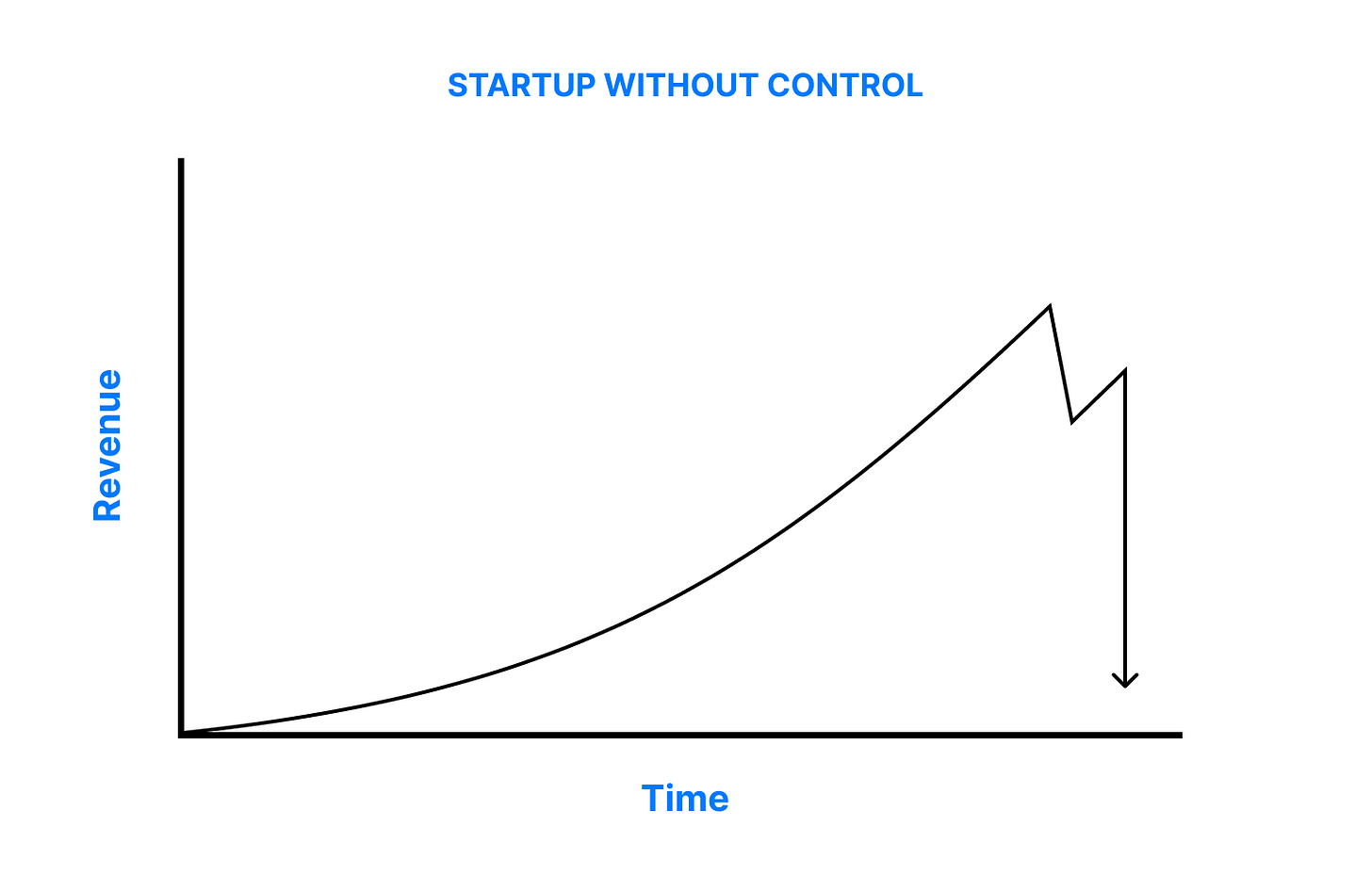

A startup that has no Control has a revenue graph that looks like this:

Control is by far the deadliest of the five “infinity stones”, often you don’t see the edge of the cliff until you’re falling off it.

In a startup that doesn’t have Control, everything goes extremely well— until it doesn’t.

It’s important to keep in mind that the Government is the ultimate platform.

The Government doesn’t have small startups on their radar, but once you get big enough you must prove to your stakeholders that you can fend off the endless stream of bureaucrats attempting to loot you.

Get big enough and the men in black come knocking wanting their “fair share”.

See Big Tech vs. U.S. Federal Government, Intuit vs. the IRS, Airbnb + Uber vs. local governments, Tencent + Alibaba vs. the CCP, etc.

Entry Barriers mean there are barriers to entry you have that other companies cannot cross to compete.

In other words, you have some advantage— or moat as Warren Buffett calls it, preventing anyone else from competing with you.

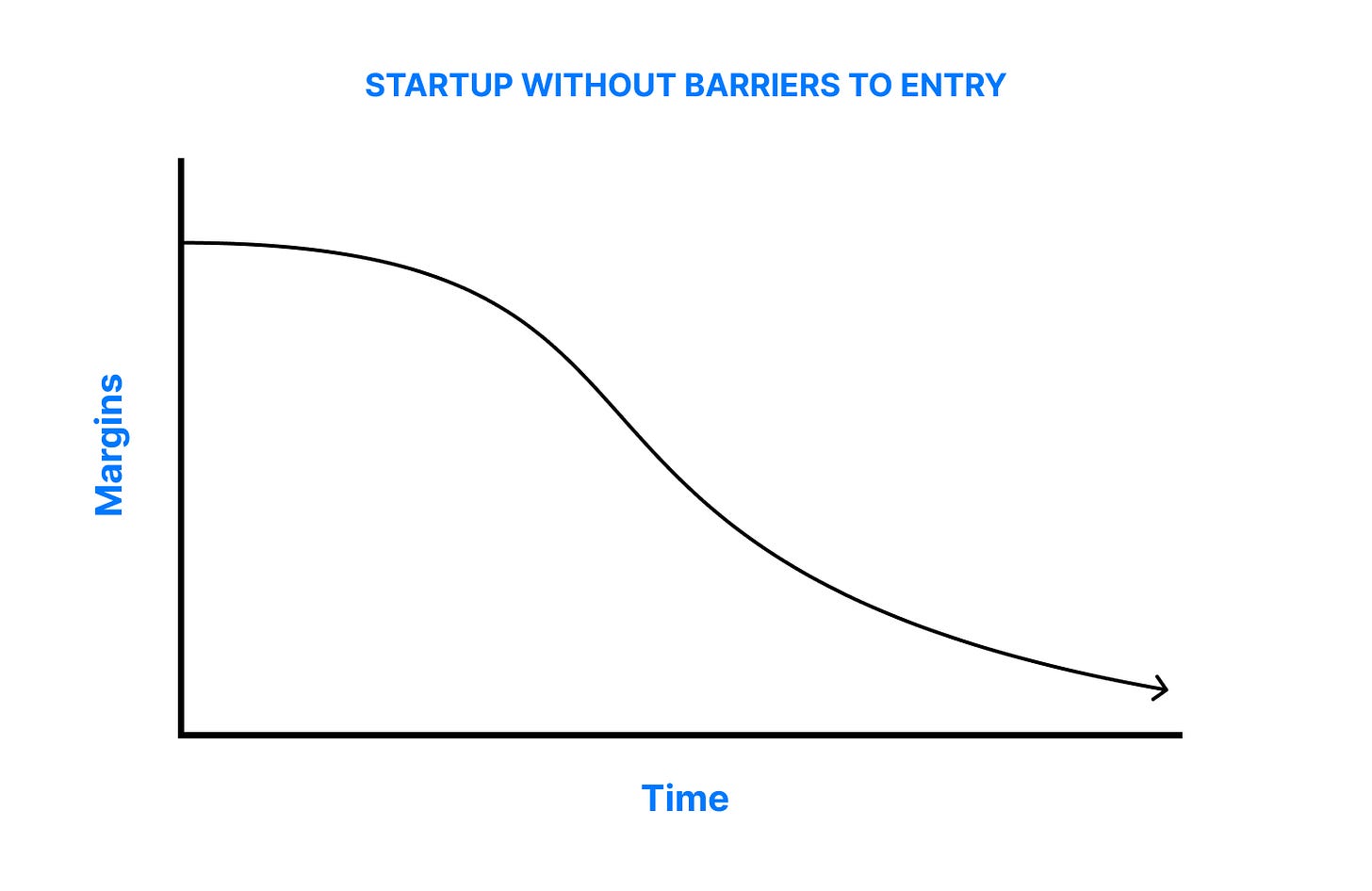

You can build an amazing world-class company with loving users, but if anyone can “start up” and take your customers away… your margins and revenue will dwindle lower and lower over time.

In other words, you’ll just be the first “business” in a new commodity market.

There are only three barriers to entry that are proven to defend businesses:

You can have so much money you can outprice everyone— preventing competition.

You can build exclusive connections with organizations like suppliers, partners, and governments— preventing competition.

You can innovate so far ahead of everyone with intellectual secrets that no one can discover them all— preventing competition.

(Think J.P. Morgan Chase’s lending algorithms fine-tuned from hundreds of millions of borrowers)

Without these barriers to entry, your revenue and margins over time will slowly diminish until they reach zero.

Necessity is the simplest concept to understand, necessity just means there is proven demand for your product by paying customers.

In other words— people need your product.

Necessity is proven by having paying customers that stay paying customers.

This can be measured by month-over-month growth rates(CMGR), net revenue retention(NRR), & overall user feedback.

You can find specifics on this in David Sacks’ substack:

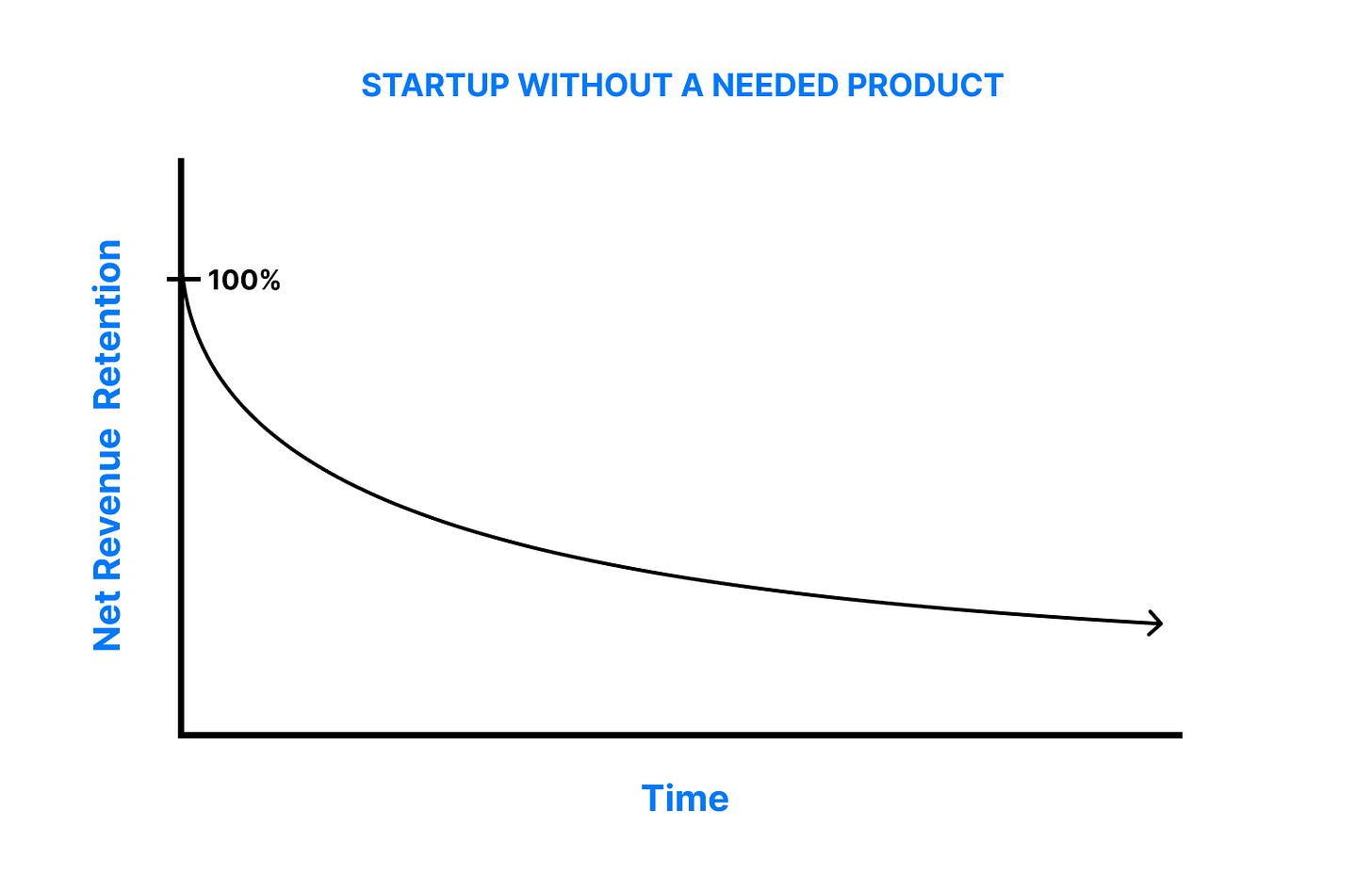

Net revenue retention is the measurement of a startup’s ability to increase spending from users over time.

A startup with 100% NRR means that over the course of a year, its group of customers that signed up a year ago keep the same level of spend.

In other words, their customers continue paying and don’t cancel their subscriptions or contracts.

Startups without a need for their product have massive problems with users trying their product… and then leaving.

A startup that does not have a true need for its product has an NRR graph that looks like this:

The optimal situation is a company’s customers spend more with them the longer they do business with them.

Time Independence — your company serves users independent of labor hours.

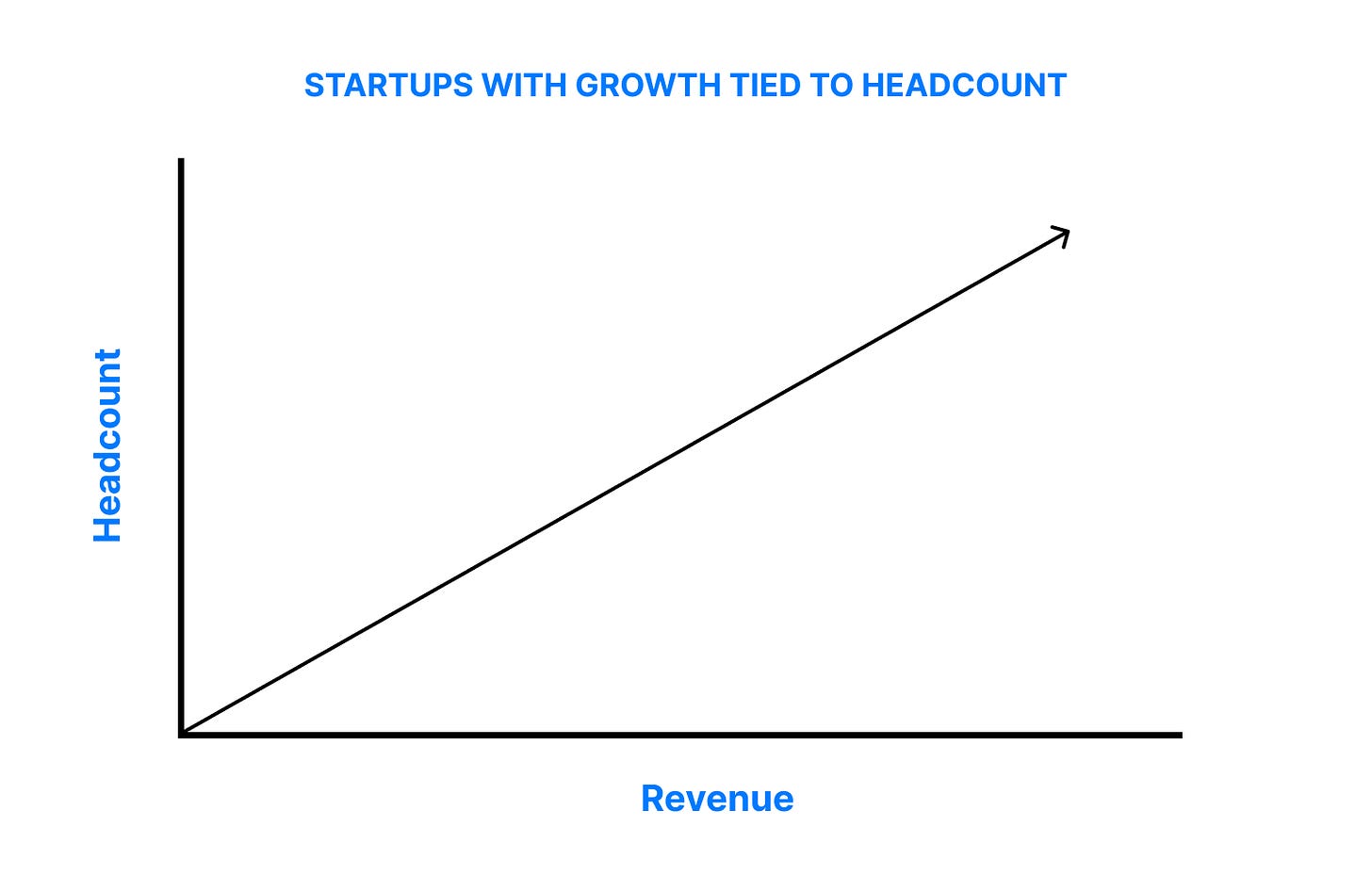

There’s a reason that consulting firms like McKinsey, BCG, Bain, and Accenture are successful… but will never be Trillion-dollar companies.

Accenture has an army of 730,000+ employees.

That’s because for every new client they sign they have to do research, design presentations, and have their partners present their findings.

In other words, for every new “user” they acquire— they must hire additional labor and increase their headcount.

Consulting firms do not make money without labor costs.

The same is true with restaurants, cafes, and almost any business that requires a physical location for customers to go to.

It’s expected that startup teams spend thousands of hours on user acquisition in the early days. You don’t have money and must acquire users not through financially expensive means, but rather through time-expensive means(i.e. outreach & startup guerilla marketing)

But eventually, you must be able to disentangle labor hours from user acquisition.

You must prove you can spend money instead of time acquiring users.

There are proven ways to work around this growth constraint such as franchising and licensing your Intellectual Property(see McDonald’s), but this is not favorable over building a technology and software business where headcount is largely disconnected from revenue.

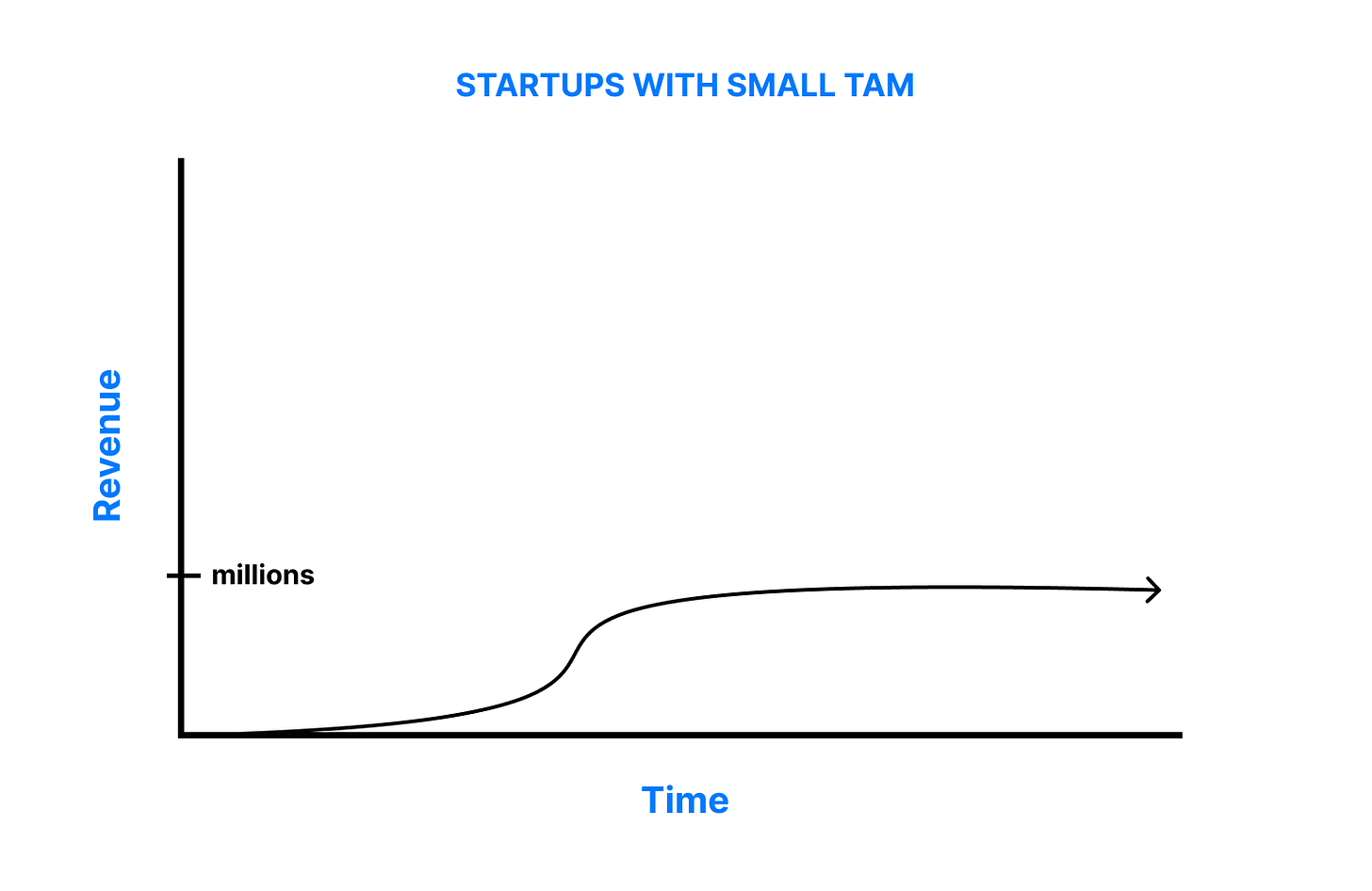

Scalability means having a conquerable big total addressable market(TAM).

This simply means that if you win, you win big— the amount of people willing to pay for your product is massive.

There are plenty of software businesses built that meet every single requirement— they have Control, Barriers to Entry, Necessity of Product, Time-Independence…

But they don’t have a huge total addressable market.

As a result, they end up as lifestyle businesses.

People such as Pieter Levels are absolute legends in the tech community.

Levels builds niche software businesses such as NomadList, RemoteOK, and Rebase (just to name a few) to hundreds of thousands of dollars in revenue per year with zero employees— before going on to build the next half-a-million-dollars per year project.

These indie hackers aren’t going after the next trillion-dollar opportunity, but they completely dominate a small market before moving to the next.

In startups having a small TAM means if you conquer your entire market your revenue is in the hundreds of thousands or millions, not billions.

Startups that don’t have scalability have a revenue graph that looks like this:

It’s important to note that most startups start out serving a small number of niche users.

“The perfect target market for a startup is a small group of particular people concentrated together and served by few or no competitors” - Peter Thiel

To become big you must begin, and compound small wins in small markets before branching out into larger markets where you dominate.

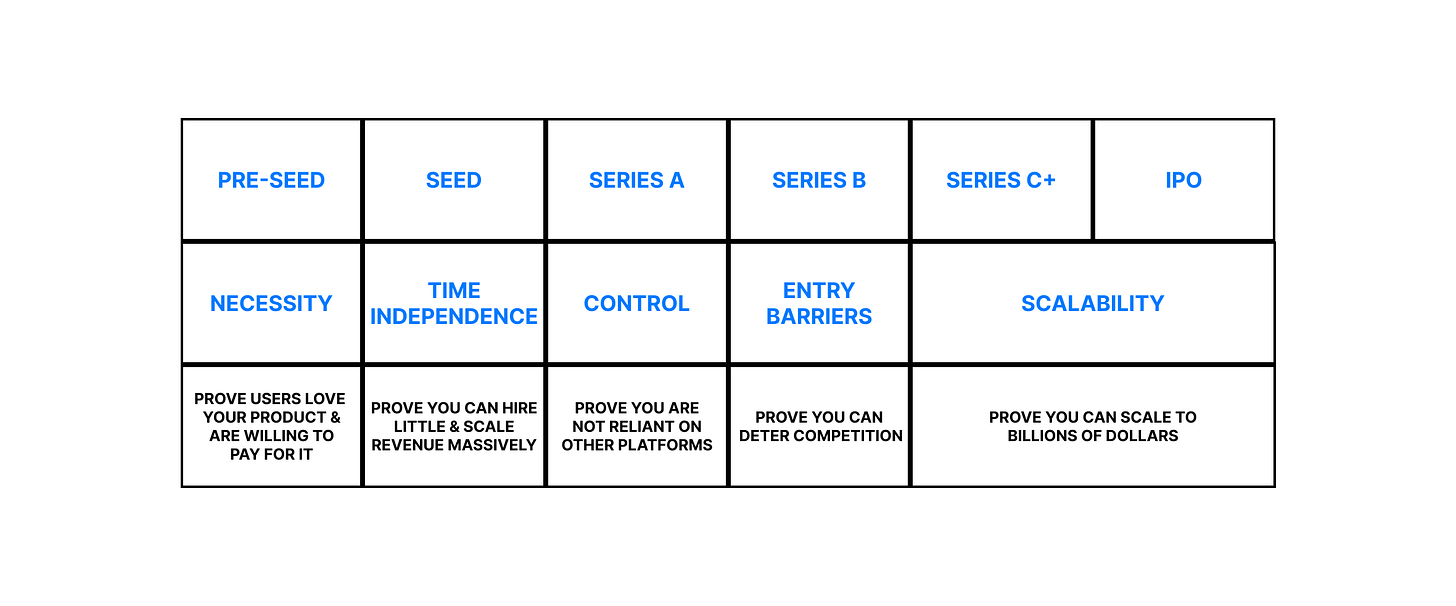

With all that covered, I want to state that no startup begins with all 5 of these “infinity stones”—most are lucky if they begin with one.

As a startup proves it can meet one requirement or make significant progress on meeting one more requirement, they raise another round of funding.

When angels, venture capitalists, and employees that invest in startups don’t need to believe a startup has all five of these “infinity stones” today.

To invest in a pre-seed startup, for example, you must see proof or strongly believe a team can build a product that users love and pay for— and have confidence they can figure the rest out.

P.S. I highly recommend checking out failory.com.

I want to end this by emphasizing— just because you’re helping build a business that lacks one of these doesn’t mean you won’t hit a Trillion dollars.

No one has the “bullet-proof master plan” figured out— no matter what they tell you.

But, you have to believe the people you’re surrounded by are smart and determined enough to figure it out in the future.

You also don’t need to start or join a company that aims to be worth a Trillion dollars.

There’s plenty of valuable, impactful, and fulfilling work to be done at companies that aren’t and won’t be worth a Trillion dollars.

If you love to stay at home with your children, run a restaurant, build cars, create art, teach Kindergarten(like my mom), or help underserved children through public service(like my dad)— that’s admirable.

Work on making the world a better place in your own way.

Metrics & Things To Look For In Each Stage

Pre-Seed(Necessity): Revenue + CMGR + NRR

Seed(Time-Independence): CMGR + Proven Distribution + Key Hires + LTV/CAC

Series A(Control): Diversified Growth + Diversified Product

Series B(Entry Barriers): Gross Margins + IP + Competitors

Series C+(Scalability): Long-Term LTV/CAC + Gross Margins + CAGR

Ranked by Danger Levels:

Control - You don’t see the revenue cliff until it’s too late.

Entry Barriers - You must quickly race to build barriers to entry before the margins of your new innovation go to zero.

Time Independence - You must build distribution methods that can acquire users with capital instead of your time.

Scalability - You must continuously position yourself to win huge markets.

Necessity - You must build products people actually use & pay for.

Disclaimer: I’m an early-stage guy(Pre-Seed through Series A). If you’re looking for takes on later-stage startups I recommend reading David Sacks’, Marc Andreessen's, and Andrew Chens’ writings.