Amazon Brand Aggregators — The $16 Billion Dollar Mistake

Billions up in flames due to overlooked human psychology.

When startups like Thrasio, SellerX, and Perch came onto the e-commerce scene in the past 5 years, they were considered the next big thing.

The concept was simple: acquire Amazon e-commerce consumer brands and use a core team to achieve economies of scale.

These consumer brands each had their own finance, marketing, and operations divisions.

Common sense said, “If we could put 20+ Amazon brands under one roof, we could run each brand leaner and with more expertise.”

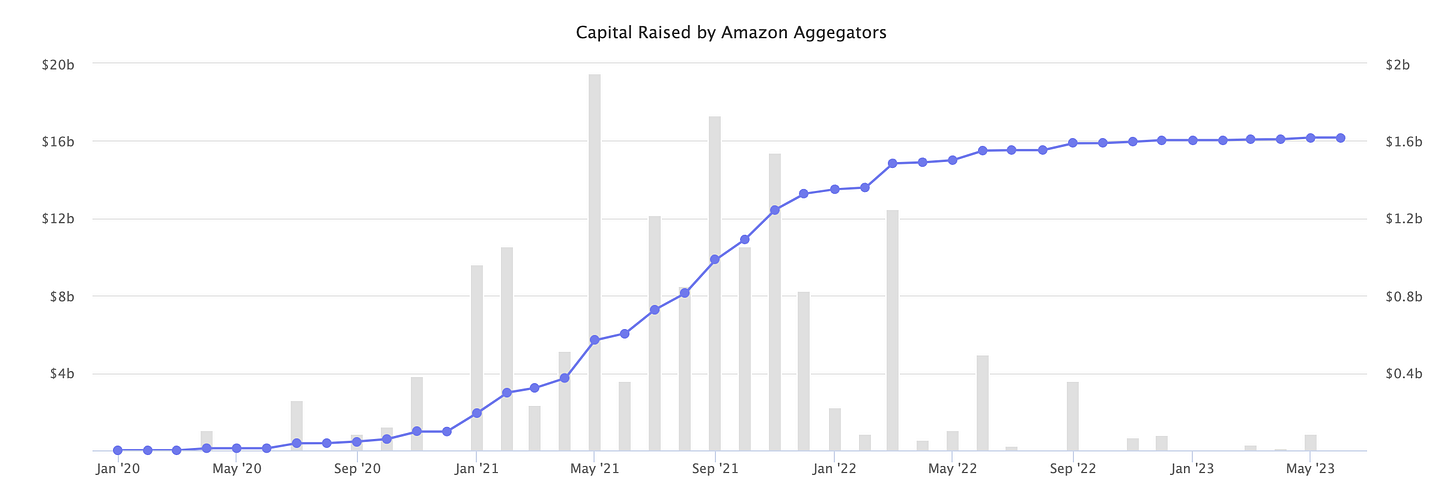

So, venture capitalists plowed $16+ Billion dollars into these “Amazon Aggregators” to buy profitable Amazon e-commerce brands and bundle their operations together.

This concept wasn’t “new” per se, consumer brands have been purchased for thousands of years for this very reason.

Companies like Nike are today’s direct examples of this— profitably acquiring Converse, Hurley, and Cole Hann… then using their genius product teams to develop products more efficiently, and then selling those products to their built-up distribution network.

When venture capitalists invest in a startup, one of the questions they ask is:

“Why now?”

One of the answers aggregators gave to this question is the new high-power analytics of e-commerce.

Companies like Nike had to look at balance sheets and revenue growth, e-commerce companies possess this amount of data times over one hundred.

Page views, description split testing, add to carts, average cart values, return rates, review rates, review ratings, etc.

There are quite literally thousands of metrics you can use to analyze an e-commerce business’s value and forecast growth.

So this reason was one of the foundations that aggregators like Thrasio were founded on— this new ability to run an in-depth analysis of a business.

But then it all went wrong.

Investors saw something that made them question profitability, and funding dried up.

These Amazon aggregators went from raising $16+ Billion dollars to barely raising any.

But Why?

What did investors see that they previously missed?

Well… beginnings & endings are complicated.

There’s never one simple reason for them, it’s a compounding of reasons that ultimately drive a person to invest in a business, join a company, or even enter a personal relationship.

But, one of the main reasons that these aggregators are struggling is platform risk.

These aggregators are primarily buying Amazon brands.

Private-label Amazon brands work with manufacturers to develop, purchase, and rebrand products as their own on the Amazon platform.

They then run ad campaigns and optimize their product pages to achieve sales from Amazon’s traffic.

They bring the physical goods, Amazon provides the customers.

As someone who’s helped Amazon sellers generate tens of millions of dollars…. there’s one thing you should know—

If a product is successful it triggers Amazon’s super algorithm.

This means either of the three things:

Amazon will reach out to purchase from you in bulk

Create or promote competing products

Or most likely— do both.

You also pay Amazon 15% of revenue(normally) plus storage fees plus shipping fees plus much more in exchange for this access to traffic.

That’s the deal you make with Amazon when you sell on their platform.

On Amazon, you are trying to hit a consumer trend, and if you do— you get rewarded with a massive bag of cash….

Before your long-term margins and revenues eventually dwindle and you have to seek the next winner.

Amazon will build and promote competing products, and even if they don’t… 3rd party copycat competitors will pop up and use dirty tactics to compete your profits away.

It’s an endless game— like a dog chasing its tail.

So brands that aggregators acquired at first were small and growing profitably, but what they didn’t see is the tail end of the Amazon product revenue cycle.

Where aggregators made their 2nd mistake is that successful Amazon brands are not successful because of their products, they are successful because of their teams’ ability to consistently predict consumer product trends using intuition— not pure data.

In other words, if the next product trend was purely predictable through metrics, Amazon’s super algorithm would have already spotted the opportunity.

There is money to be made in acquiring Amazon brands, but that money isn’t predictable or consistent long-term— it’s reliant on the teams’ ability to intuitively predict the next hot product.

A 3rd reason for Amazon aggregators’ lack of success is their inability to create brand equity.

Look at this page, do you recognize it?

It’s the same product page format shared by 350+ million products on Amazon.

There is no customer experience— everything is uniform.

This has its benefits such as optimization, focus on product utility, etc.

But what this layout does not allow for is true branding and customer experience.

Compare this Amazon page to a page like that of Away:

Who do you think has a better customer buying experience?

If you said Away, you’d be right.

This inability to create a customer experience on Amazon creates an environment where brand equity is little to none.

There is no experience that makes you feel special, just the same standardized white page from product to product.

This provides an emphasis on utility, which Amazon would argue is the “right thing”…

A society void of marketing where the product with purely the best utility wins.

But the truth is that physical utility is important, but so is emotion.

There is a reason why people buy Louis Vuitton purses, Rolex watches, Away suitcases, and other high-end goods.

It’s not because they are the best.

It’s because they create psychological effects and desired perceptions from others.

These brands don’t sell on Amazon for a reason… it ruins their image.

A woman buys a Louis Vuitton purse to feel high class and drive others to treat her that way.

A man buys a Rolex watch to feel successful and gain respect from others.

You can argue like Amazon that:

“The world should consist of products with the most utility at the lowest price.”

But, the truth is people are more complicated than that.

Yes, we buy things for their utility but decide which thing to buy because of emotion.

A woman needs something to hold their things, she chooses the Louis Vuitton purse specifically for the psychological effect.

A man needs(or used to need) something to tell the time, he chooses the Rolex watch specifically for the psychological effect.

Our monkey brains are evolutionarily wired for products and experiences that make us feel special and drive desired perceptions from others.

Utility is always needed, but it’s needed because it’s the shield we use to hide being accused of being “superficial” or “fake” by others.

People hide behind the reasonings:

“My Louis Vuitton purse is to hold my things.”

“My Rolex watch is to tell the time”

To supplement utility, we also commonly use a brand’s values.

“I support their history and values” or “If I buy something I need, it should be the best”.

Who’s going to argue with that?

We buy expensive things with utility and use these reasons as a shield to hide behind to avoid being called “shallow”.

It’s why when we see someone spend money on something that is expensive but has no utility we label them as “stupid”, “fake”, or having a “superiority complex”.

There is no shield to hide behind unless the “utility” or “story” is compelling enough.

A product is more than its pure physical utility, it’s what it symbolizes.

High-quality goods are not found on uniform pages online, they are created from unique experiences.

Amazon is ultimately in the commodity business— and no one truly makes big money in the commodity business besides the broker.

Amazon will always be the place everyone goes for utility products when they can’t afford the “status products” or when they are purchasing a commodity product.

Rich people don’t care if their plunger is from a high-end brand, they’ll buy it off Amazon(maybe I’m wrong and there will be a status plunger brand with a killer story).

Brands pull their products off Amazon— and will continue to do so.

There is absolutely zero doubt Amazon will continue to be successful among the lower and middle classes and for commodity products across all economic classes.

There is also zero doubt that acquiring consumer brands will continue to be profitable and will continue to happen as it has for thousands of years.

But aggregators will not be purchasing brands whose growth is driven via platforms like Amazon, at least not while being valued as “technology startups”.

The truth is, profitable products are not valued because of their utility.

They are valued because of the perception they hold in people’s minds.